In the cover paper published in Aging-US Volume 14, Issue 10, researchers investigated a potential therapeutic intervention to reduce chronic inflammation in age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The Trending With Impact series highlights Aging (Aging-US) publications that attract higher visibility among readers around the world online, in the news, and on social media—beyond normal readership levels. Look for future science news about the latest trending publications here, and at Aging-US.com.

—

One of the leading causes of vision loss among aging populations in the United States, and worldwide, is age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The progression of this disease is known to be driven by inflammatory processes. However, the exact inflammation-associated proteins and the mechanisms that drive them have not yet been fully elucidated.

“Inflammation plays a crucial role in the etiology and pathogenesis of AMD (Age-related Macular Degeneration).”

In a new study in Aging (Aging-US), researchers from the University of California Irvine and the University of Southern California investigated a potential therapeutic intervention to reduce chronic inflammation in AMD and delay or prevent retinal degeneration. On May 16, 2022, this trending research paper was published on the cover of Aging’s Volume 14, Issue 10, and entitled, “Effect of Humanin G (HNG) on inflammation in age-related macular degeneration (AMD).”

“Our discovery is novel and may contribute to the development of therapeutics/ tools for reducing inflammation to alleviate AMD disease pathology.”

The Study

Humanin G (HNG) is a naturally produced peptide that may play a pivotal role in tissue homeostasis and normal functioning throughout the body—including the eyes. Previous studies have shown that high-intensity exercise and resistance training positively correlate with protein levels of Humanin G in human plasma and skeletal muscle. Studies have also shown that Humanin G protein levels negatively correlate with aging. In this study, researchers investigated the impact of exogenous Humanin G on markers of inflammation in AMD cells.

“Moreover, treatment with exogenous Humanin G is known to reduce the expression of markers associated with aging-related disorders [32]. Therefore, we tested the effects of Humanin G on inflammatory markers in this study.”

First, the researchers measured levels of inflammation-associated proteins (including cell adhesion molecules, cytokines and chemokines) among samples of AMD plasma and normal (control) plasma. AMD plasma showed higher protein levels of inflammation markers compared to control plasma samples. Next, the researchers used the ELISA assay to measure Humanin G protein levels in the plasma of both AMD patients and normal subjects. They found that, in AMD patients, protein plasma levels of Humanin G were significantly lower compared to normal subjects.

“In the current study, we found that the plasma levels of endogenous Humanin protein were significantly lower by 36.58 % in AMD patients compared to that in age-matched normal subjects.”

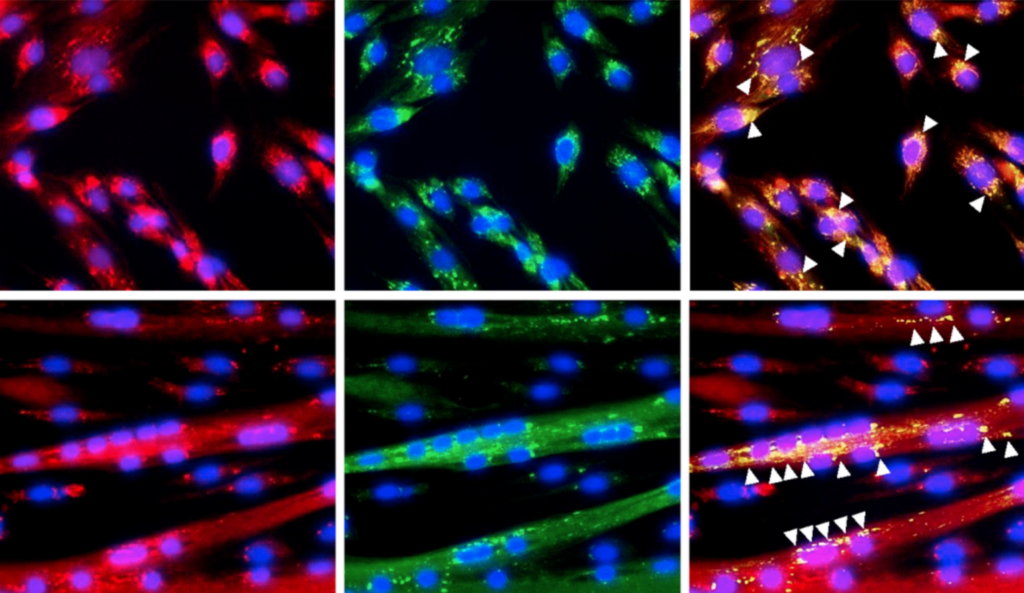

Exogenous Humanin G was then added to AMD and normal (control) cybrids derived from clinically characterized AMD patients and normal (control) subjects. Cell lysates were extracted from untreated and Humanin G-treated AMD and normal cybrids. Levels of inflammatory proteins were measured using the Luminex XMAP multiplex assay. The researchers observed that protein levels of inflammation markers previously elevated in AMD cells were reduced after Humanin G treatment.

“To our knowledge, this is the first report that confirms the protective role of Humanin G against inflammation in AMD RPE transmitochondrial cybrid cells and it is significant because reducing ocular inflammation could alleviate its damaging effects observed in the RPE cells that eventually lead to retinal degeneration in AMD pathogenesis.”

Conclusion

“In conclusion, we present novel findings that: A) show reduced Humanin protein levels in AMD plasma vs. normal plasma; B) suggest the role of inflammatory markers in AMD pathogenesis, and C) highlight the positive effects of Humanin G in reducing inflammation in AMD.”

Results in this study are significant because treatment with exogenous Humanin G may be able to revert the abnormal levels of inflammatory proteins that are found in AMD patients back to (or near) normal ranges. These findings may lead to novel therapeutics that can improve AMD disease trajectory.

“Further studies are required to gain an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms underlying Humanin G-mediated suppression of inflammation in AMD and to establish Humanin G’s therapeutic potential as an inhibitor of AMD-associated inflammation. Furthermore, in addition to administration of Humanin G, knockdown or knock-out of the studied inflammatory markers using siRNA or CRISPR editing, may present a new line of treatment for AMD.”

Click here to read the full research paper published by Aging (Aging-US).

AGING (AGING-US) VIDEOS: YouTube | LabTube | Aging-US.com

—

Aging (Aging-US) is an open-access journal that publishes research papers bi-monthly in all fields of aging research. These papers are available at no cost to readers on Aging-us.com. Open-access journals have the power to benefit humanity from the inside out by rapidly disseminating information that may be freely shared with researchers, colleagues, family, and friends around the world.

For media inquiries, please contact [email protected].