Following theSecond Interventions in Aging Conference, meeting organizers Dr. Brian Kennedy and Dr. Linda Partridge discuss their overview of the meeting proceedings that was published by Aging in 2017, entitled, “2nd interventions in aging conference.”

Behind the Study is a series of transcribed videos from researchers elaborating on their recent oncology-focused studies published by Aging. Visit the Aging YouTube channel for more insights from outstanding authors.

—

Dr. Brian Kennedy

I’m Brian Kennedy, I’m a professor at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and a visiting professor at National University of Singapore.

Dr. Linda Partridge

And I’m Linda Partridge and I’m Director at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging in Cologne, Germany. And also Director of the Institute for Healthy Aging at University College London.

So, Brian, how did you get into aging research?

Dr. Brian Kennedy

The funny thing was when I went to graduate school, I’d worked in yeast as an undergraduate, and I decided that I was not going to work in yeast anymore. But the more I realized about how difficult it was to work in mice, the more I wanted to work in yeast. And so there was another graduate student and I that wanted to go to Lenny Guarente‘s lab, and we decided to work in yeast and we wanted to figure out something completely crazy to do.

And we came up with two ideas: One was yeast apoptosis, which was a little weird for a single-celled organism and the other was aging. And we decided that aging was the least-

Dr. Linda Partridge

Mr. Nobel Prize.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

It’s true. We decided that aging was the least implausible of the two. And so we did that, but there’s a whole field on yeast apoptosis now too, so I guess we would have been okay. How about you?

Dr. Linda Partridge

Well, I got into it crabwise, really, because I started out life as an evolutionary biologist. So from the evolution point of view, it’s a completely weird trait because development produces a wonderfully functioning young organism and then it all goes to hell. You’d think it would be a lot easier to maintain it and to produce it in the first place. So I became very interested in how aging evolves and it is indeed really peculiar it’s almost certainly given what we’ve learned recently about the mechanisms of aging, actually bad effects in old age of genes that are good in the young. So I think that’s pretty interesting if you think about it as genes driving the old organism too hard to do the kinds of things that young organisms can do very well. I think it makes quite an easier process to think about, put it that way.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

And what we started the puzzle, both of us have worked on this a lot is, you know we’ve been trying to show that the pathways that are modulating aging are conserved. And it’s always kind of a puzzle that there’s so much conservation if this is a trait that evolution never really cared about that much. So it’s… I’ve never quite got that satisfied in my mind. What do you think about that?

Dr. Linda Partridge

I guess what I think is that the processes that you and other people have come up with, there are ones that do drive good things in young organisms. So the things that make for growth, for reproduction, for strong immune responses, for effective muscles and movement, all the things that young organisms have to do. But they seem to be set at too higher level when you get old, and I think that way it is actually quite easy to understand why it’s evolutionarily conserved because presumably the kinds of genes that control growth and reproduction evolve very early on.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

I agree. I actually argue with people that aging is going to be easier to modify than disease. So I think it’s going to be easier to keep people healthy than it is to wait until they get sick and try to treat them and make them better. I think of it as very simplistically as a state of homeostasis versus disequilibrium, you know, while you’re still relatively healthy, it’s fairly easy to tap into these pathways … relatively easy to tap into these pathways … and try to maintain that. But once you get into a state of disequilibrium, which I would call chronic disease of one sort or another, then you’ve got a problem. You’re kind of fighting entropy at that point and trying to put things back together again is very difficult.

Dr. Linda Partridge

Yes, it’s very interesting talking to colleagues in other areas about that idea because one gets a kind of ‘yuck’ response. So does that mean that humans are going to have to take pills when they’re healthy to prevent disease? You can point out that people do that already around statin and aspirin and things that lower high blood pressure. None of these are dealing with disease states, they’re in anticipation of possible disease states and trying to prevent them. So there’s plenty of taking pills to prevent things already, but for some reason, when you talk about it as a likely outcome of research into aging, there’s quite often a kickback, even from other scientists.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

I think most of the things we take, you know that are really working effectively really are aging drugs as much as they’re disease drugs. So you mentioned aspirin, but not just that I mean, look at statins, look at beta- blockers, look at early diabetes drugs like Metformin. All of them are targeting early risk factors for chronic disease, and I kind of feel like these risk factors are right at the interface between aging and disease itself.

Dr. Linda Partridge

They’re right on the nexus of the way in which aging acts as a risk factor for disease, and I think the other thing about them is that it’s quite clear that they’re turning out to have off-licence effects. Most of these drugs have a much broader therapeutic range than they’re generally used for. Which is exactly what you’d expect if they’re in there in that nexus between aging and disease.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

So what’s exciting to you now in your research? Where are you going in the next five years?

Dr. Linda Partridge

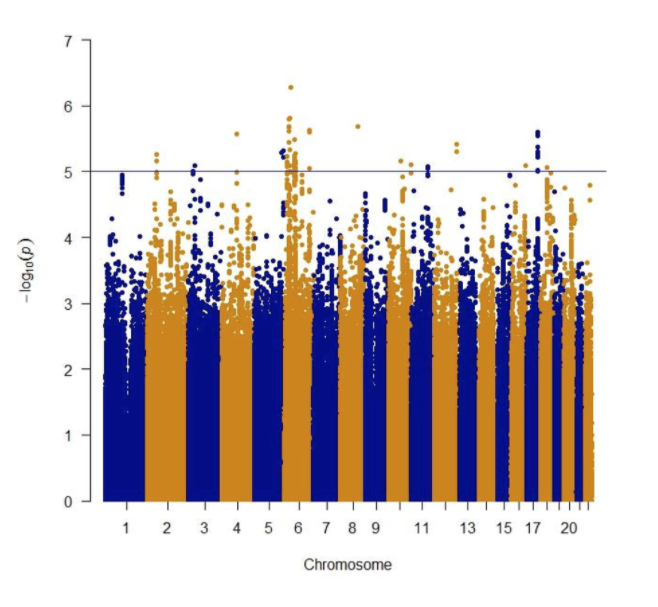

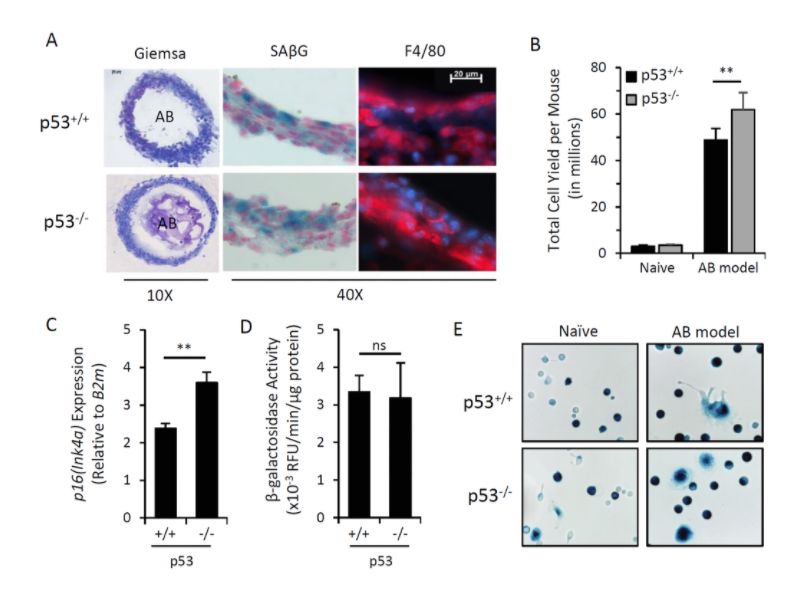

Well, funnily enough, I’m very much into drugs. So we’ve been doing quite a lot of drug work with drosophila and based exactly on this idea that mechanisms of aging are conserved. We’re starting to take a number of these drugs into mice, but also starting to do some big database stuff with humans, looking at particular pathways that have come up in the model organisms and asking whether SNPs associated with those pathways in humans ones that are either likely to increase the activity of the pathways concerned or decrease it or associated with particular types of disease risk.

So one can do this process called Mendelian randomization, which in theory gets rid of a lot of the effects of genetic background and focuses on a particular SNP. Now I think there’s enough data coming in on humans that we can really start to do the population genetics on these pathways, and I’m terribly excited by that.

What about you?

Dr. Brian Kennedy

Well, I have two goals right now. One is to try to go back to the simple organisms and really take a systems approach and try to take a yeast cell for example, and be able to describe all the features of aging, not just one gene at a time. And so we’re working a lot in sort of systems biology approaches there, but I think the main goal I have is-

Dr. Linda Partridge

Do you mean you’re looking at gene combinations or how are you doing it?

Dr. Brian Kennedy

Yes. Gene combinations, but also working with collaborators to look at how signaling pathways change with age to start to really understand longitudinal processes in a yeast cell. So the idea is to combine that with the genetic data and try to put the puzzle together.

Dr. Linda Partridge

I think that’s interesting.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

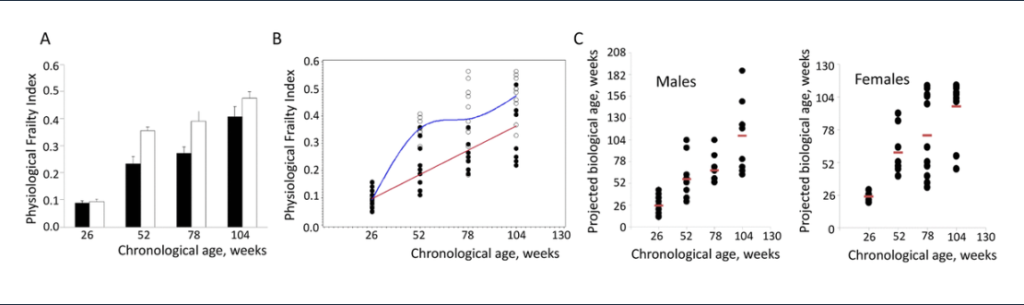

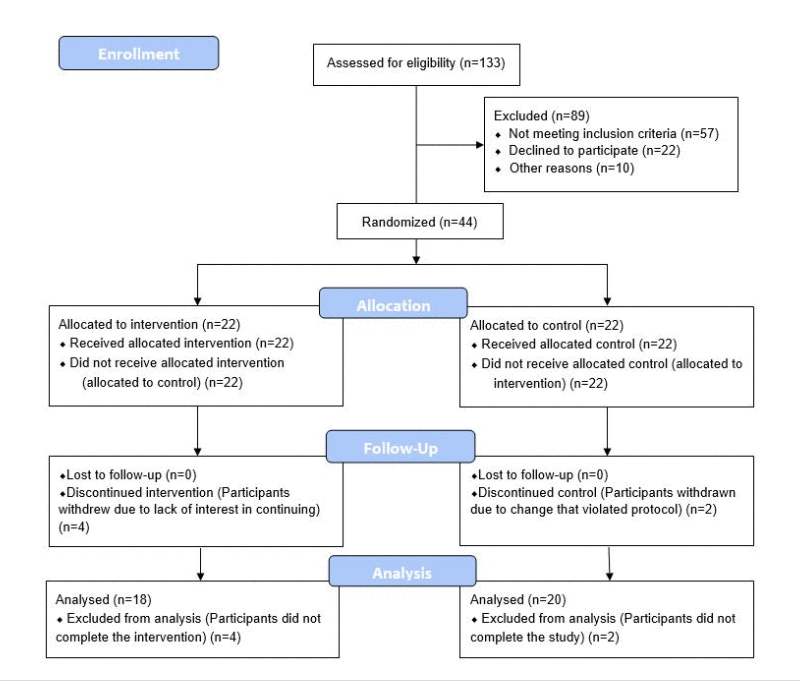

My main goal really is to get human and to start testing interventions in humans because I think we have enough knowledge now that we have things that are likely to work and we have reasonable candidate biomarkers, none of which are completely validated, but I feel good about some of them. And if you put that together, I kind of see it as a lock and key fit. You know we’ve got a bunch of interventions which are potential keys, and we’ve got a bunch of biomarkers which are potential locks, and we have to figure out which keys fit in which locks. So I’m looking at strategies to really test that in humans, either through academic research or through private companies.

Dr. Linda Partridge

So do you think companies are going to be interested in doing the kind of research that would target more than one disease, or do you think the way in is going to be to go for particular disease states? How do you think we should do it, operationally?

Dr. Brian Kennedy

I’d much rather target healthy aging or health span or prevention of multiple diseases. And I think there are companies that are thinking about that now, but they’re still relatively small generally. I think PhRMA kind of walks up to that ledge and looks over and then backs up. But eventually I think that it’s going to happen. I think what we need is some evidence that we can really modulates aging pathways. And that’s where this biomarker strategy or the kinds of things that [inaudible] is doing to get multiple disease parameters simultaneously in clinical trials. Those kinds of things, I think, are you just need a couple of success stories and then people start to get it. So I’m agnostic as to whether it’s done academically or privately, I just want to make it happen and so you know.

Dr. Linda Partridge

So what do you think about… We know so much from the animal studies about rapamycin now we probably know more about that than any other drug in the context of aging. Do you think there are going to be more clinical trials with rapamycin for off-license applications? Do you think it would be a trial for Alzheimer’s for instance?

Dr. Brian Kennedy

You know, there’ve been a lot of talk about trials for Alzheimer’s and I don’t think one has gotten started yet. But I think you’re going to start to see more and more of this. Then of course, there’s a lot of research to try to figure out how to either dose rapamycin or everolimus, which is the first generation of that rapalog in a way that doesn’t have the toxicity or to develop new drugs that have the efficacy without the toxicity. So I think both of those approaches are moving forward.

Novartis just spun off a small company to try to do this, and so I think that there’s renewed interest in trying to inhibit mTOR, but there’s still a lot of open questions about how it’s going to be best to do that. But having said that the number of potential indications, I mean, not to mention aging itself is so large that there’s clearly value into doing this successfully. So I’m pretty excited about where that’s going to go. I think that’s only one of a bunch of pathways though and you’re looking for new drugs and new pathways, and I think we’re going to find that there are a lot of different potential entry points for intervention in aging as we go forward.

Dr. Linda Partridge

I think it’s a time of great excitement. I just hope that some of the human trials get done while I’m still active. I’d love to see some successes with people.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

But you will be active for at least 20 more years, so …

Dr. Linda Partridge

Lots longer if somebody comes up with a pill.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

You know, that’s why I think doing this Fusion Conference has been so fun. You know, we’ve done two of these now in Cancun, and the idea is to bring different groups of people to look at different strategies for interventions in aging. I think that the conferences are relatively small, but we try to recruit a wide range of people. So we get people discussing different kinds of ideas that don’t normally talk. That’s what I think the strength of it is what do you think?

Dr. Linda Partridge

I agree with that. I really like the format of those conferences because they have a low upper limit on the number of delegates deliberately. So that most people can give talks or posters and there’s plenty of time for discussion. And what I noticed at those meetings correspondingly is that the discussion is very intense. Almost everybody talks to everybody else at some point during the meeting. So there’s real interchange of ideas as you say, between people who we deliberately invite from different areas, and I think it’s been a great success and it’s also been very nice to see it going more and more translational. There is more and more interest in mechanisms that are going to give rise to preventative measures rather than just the basic research, which has been fantastic and was necessary to get anywhere. But people really are trying to push it into helping people now. And I find that very exciting. So yes, I think meetings are great.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

Yes, I know, and I think as we go forward with these meetings, we’ll probably continue to try to emphasize these human intervention studies as much as possible.

Dr. Linda Partridge

I think that’s very much a specialty of that meeting.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

Because there are other meetings that really focus on the basic biology of aging, but this is really trying to get at the next step.

Dr. Linda Partridge

Yeah. Yeah. It’s particularly good when we can get basic scientists and clinicians together, I think. And also people from the various companies who might do something about the discoveries. I think it’s a very good mix of people that way.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

I can’t, you know, in my better moments, I think that we’re almost right at a tipping point where we’re going to push over this wall and then all of a sudden everybody’s going to be saying, oh, targeting aging is common sense in 10 years. I still have the bad moments where I feel like the little soldier walking into the wall and never go anywhere too.

Dr. Linda Partridge

Yes. I fluctuate between those two points as well, but I find myself feeling optimistic more and more often seeing what’s happening.

Dr. Brian Kennedy

That’s good. Well, it’ll be exciting to see where the field goes moving forward…

Dr. Linda Partridge

Yeah, indeed. Indeed.

Click here to read the full meeting report, published by Aging.

WATCH: AGING VIDEOS ON LABTUBE

—

Aging is an open-access journal that publishes research papers monthly in all fields of aging research and other topics. These papers are available to read at no cost to readers on Aging-us.com. Open-access journals offer information that has the potential to benefit our societies from the inside out and may be shared with friends, neighbors, colleagues, and other researchers, far and wide.

For media inquiries, please contact [email protected].